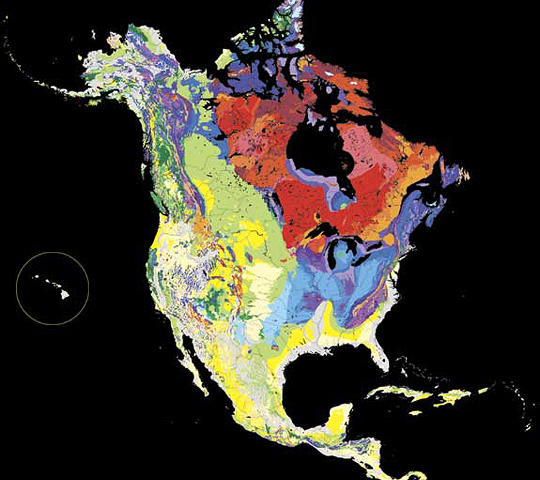

Geologists are lucky in that their profession gets to study some of the oldest material available to observation, but just like every topic concerning origins, it is fraught with controversy and competing claims. Such elements were a prime focus of this past week’s Van Tuyl lecture by Dr. Stephen Mojzsis of the University of Colorado. Mojzsis has had the distinction of working on the rocks of the Nuvvuagittuq Supercrustal Belt, or the NSB for short. The rocks of the NSB are some of the oldest in the world, dating around 3.8 to 4.2 billion years old. The NSB exists within the Canadian Craton, which is by far one of the oldest blocks of geological material in the world.

For most of the world, the true geology is covered with many meters of dirt, sand, or water and can be extremely hard to get to. Luckily for those working on the NSB, most of the overlying material was removed by glaciers. The rocks themselves steal the show, where the rocks around Golden can be complex due to the Rocky Mountains. “Its complicated,” joked Mojzsis, “if you’d been around this long, you’d be complicated too.”

Luckily for those in the crowd who did not have an understanding of advanced metamorphic rock types, Mojzsis provided involved descriptions and hand samples of the rocks. All of the rocks of the NSB are metamorphic in nature, many of them having undergone multiple instances of metamorphism in their many years on Earth. When rocks undergo metamorphism, they change their mineral components, especially under higher grades of metamorphism. Along with changes in mineral composition, the rock itself will usually deform and fold, which can prove especially challenging for mapping; “You don’t just go in and stash and dash, you need to make a map and a plan of attack,” offered Mojzsis.

One of the more interesting discoveries by Mojzsis and his team involved a certain deposit type called banded iron formations. Banded iron formations are interesting in that the oxygen proportions in the atmosphere prevent the iron bands from forming today. On the other hand, these deposits formed quite readily early in the Earth’s history when the atmospheric composition was drastically different. According to Mojzsis, the presence of the banded iron formations at their Inukjuak site proves that there could be microbial life at the time of deposition 3.8 billion years ago. “People have tried [to form banded iron formations without life], when you do that, the reaction doesn’t go,” revealed Mojzsis confidently, “when you put a micro-organism in, it works… it is not proof but it is consistent.”

The other element of controversy in the project is the exact timing of the metamorphism. Mojzsis and his team were shocked to discover after they worked out their findings that another team had reported the rocks at the Inukjuak site were approximately 500 million years older than originally measured. In this case, these rocks would be the oldest in the world and might have predated the period in the history of the Earth termed the late heavy bombardment that would have effectively resurfaced the planet. Fortunately for Mojzsis and his team, the other data seemed fairly scattered and unreliable, while their original data was more concise. To work out the problem, his team returned to the NSB along with the competing team to search out the solution. After some more work with zircons and clarifying of rock types, the data appears to favor the 3.8 billion age offered by Mojzsis and his team.

The final discovery of importance was the actual rock type. Originally it was thought that the rocks were mafic in origin. Mafic is a type of volcanic rock that is not very mature. By looking at the components of the rock, Mojzsis and his team determined that the rocks were not actually mafic in nature, but instead sedimentary. This is interesting given the extreme age of these rocks.This implies that sedimentary processes were already occurring at the time of deposition and the source of these rocks may be even older.

'Digging Deep into the Earth’s Past' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!