Formulary Glyphs

The next stop on the public art tour is a building on campus that is so old it predates the Art in Public Places Program by sixteen years. Yet to make up for this, it had two pieces installed in back-to-back years at the end of the last decade. The first piece of art installed in 1998 is found in the Coolbaugh Atrium. Hanging over the various shelves filled with Copies of High Grade, The Oredigger, chemistry magazines, and other periodicals are the six bronze and aluminum wall reliefs that makeup Formulary Glyphs. Artist William Vielehr created the six reliefs using the lost wax process of casting. This process of casting creates slightly warped and abstracted castings of the module originally carved in wax. The goal was to create wall hangings reminiscent of petroglyphs, the prehistoric wall carvings made by early man. Upon closer inspection, some of the glyphs stand out as English letters, Greek letters, and numbers. Though never comprising a complete sentence or mathematical function, Vielehr intended their implied importance to speak to the viewer. Despite being frozen in time and cast in bronze, these symbols retain their meaning because, as cultures, we assign value to them to communicate and humanize the world. In creating Formulary Glyphs, Vielehr wanted to turn something comforting and familiar to the students of mines into another unknown to be scrutinized.

Arbor Vitae

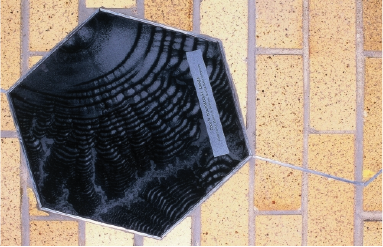

This next piece of public art is unique in how it spans from the outside to the inside of the building that it adorns. It’s likely that a large number of the students who visit Mines will not only see this piece but also walk over it. This large volume of traffic results from many first-year students heading to general chemistry lectures or to take a test in the most infamous testing room of them all, Coolbaugh 209. Despite this, few students would be able to name the piece as the plaque for it is also on the outside of the building and obscured by a shrub. For those daring enough to wade through foliage, the plaque reveals that the name of the art is Arbor Vitae, and the artists responsible for its creation were Theodore Prescott and Peter Richards. The exterior portion of Arbor Vitae is a topographical satellite map of Colorado that has been carved into black granite. The interior part of Arbor Vitae is the part that inspired its name. Arbor Vitae is Latin for “tree of life” and in biology, it is the name for the white matter found in the cerebrum that resembles the branches of a leafless tree. The interior art consists of black granite hexagons arranged in a branching pathway reminiscent of the branches in the tree of life. The placement of these black hexagons is based on a polymer chain developed by a past Colorado School of Mines professor, Daniel Knauss. Artist Peter Richards intended for half the black granite tiles in the branching polymer be organic systems or inorganic systems. In the center of the tiles is a human brain being held by a pair of hands, titled “Self Portrait” by Helen Chadwick. On the left side of “Self Portrait” the images are organic and on the right side, the images are supposed to be inorganic. However, since 1999 when the art was first installed a granite tile displaying a computer chip was added to the right side, ruining the artist’s intended organization of the images. The artist’s purpose of laying out the organic and inorganic systems this way was to express patterns in the natural and manmade environments, and the way that learning can occur by considering the branching paths that relate systems.

'Public Art Series: Coolbaugh Hall' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!