The three oldest pieces of public art on campus have more in common than just their age. The trio was commissioned for the Art in Public Places requirements of Berthoud and Stratton hall renovations in the mid-1980s. This is unique as most projects today use all of their budget for a single piece. However, the $50,000 budget was used to fund a painting for each hall and a sculpture. Stratton Hall received an acrylic painting by Clark Reichert, and Berthoud Hall received an oil painting by George Woodman. Both the paintings were unveiled before the sculptor for the final piece of this artistic trio was chosen.

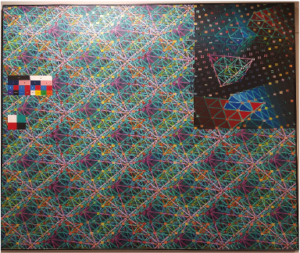

The painting in Stratton Hall is titled Knowledge Truss and was unveiled in 1986. As the name suggests, Knowledge Truss depicts the aspects that Reichert believes supports the progression of knowledge and innovations in modern society. These aspects include, “Art, Religion, World, Media, Science, Philosophy, Technology, and Sociology”, according to a key in the painting. As a result of the colors representing each aspect overlapping and connecting repeatedly, a larger cubic lattice structure emerges.

In Berthoud Hall, the painting by Woodman contains less social commentary. The painting has the simple name Summer and is the oldest piece of public art on campus. It was dedicated in 1985. This painting features several intertwined shapes on a pastel background. Together with Knowledge Truss the two paintings accounted for $10,000 of the $50,000 budget.

The last piece is one of the most mysterious pieces of public art on campus resides in one of Mines’ most popular open spaces. On the far northeastern end of Kafadar Commons sprouting up from a berm flanked by trees, are the three pillars of the sculpture titled Of the Earth and Man. The sculptor, John T. Young, was selected from 30 national artists recommended by the Colorado Council on Arts and Humanities in 1987. It was completed 2 years later in 1989. Of the Earth and Man is composed of three very different pillars laid out so that they encourage viewers to walk in between them to create a sculpture that could be experienced from many different angles.

Each pillar represents a way in which man interacts with nature to forward his own goals. The first pillar, a rough-cut granite pyramid, represents man’s love for natural landmarks and how society draws inspiration from them. For Young the pillar was not just a random representation of primal nature, but “refers most closely and directly to Table Mountain” in a nice nod to the beautiful landscape of Golden. In the rugged pillar, there is a steel rod that holds open a seam. Being able to peer into this pillar represents how man is studious and probing of the natural world. The next pillar is a smooth diamond with steel supports. Steel is used in this pillar to connect the diamond shape to the base and provide further support. Young highly values this transformation of raw nature into something that serves humans and the use of other technology to further augment primary products of nature. The making of something new and valuable from natural resources is “directly referring to engineering” as young wrote in his design rationale, “and to Man’s abilities to create Magic and Structural intrigue.” The last pillar is a traditional Greek column, and refers to the “Classic scholars of ancient Greece”. The pillar represents the pursuit of knowledge and the refinement of our understanding of the natural world. Young took great care in designing the pillars of Of the Earth and Man and its integration with the surrounding landscape. Young wanted to remind Mines students that as they move into the study of phenomena in sterile labs, they are still on some level manipulating natural systems and drawing inspiration from the environments around them.

Upon completion of the sculpture, Young did not leave a statement with the Colorado Art in Public Places Program. This had caused the meaning of the sculpture and much of the design process to be lost. Thankfully a member of the Mines office of design and construction along with the project manager for the Colorado Art in Public Places Program helped uncover the meaning of the piece. As part of the proposal Young submitted to the Colorado Art in Public Places Program, he included a design rationale explaining the intent of his work. Young made it clear that while developing the sculpture he struggled with creating something eye-catching on the flatlands of Kafadar Commons without it appearing “’plopped’ into place.” To solve this problem, Young designed the berm and rough stone bases to make it appear that the earth was swelling up in that location and that the piece emerged from the ground instead of being placed on top of it. Young’s exact intention for Of the Earth and Man could have changed, but the symbolism in his artist rational is still very interesting.

'Public Art: Of the Earth and Man, Summer, and Knowledge Truss' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!