The impact of the falling price of oil will have far reaching effects on the Mines’ community as the oil and gas industry hired 35 percent of Mines graduates starting industry or government jobs following the 2013-2014 school year.

This statistic from the most recent Career Center Annual Report includes students from every academic department at CSM. Even if the recent petroleum industry downturn does not affect you directly, it probably affects your friends and colleagues.

As the markets closed on the last Friday in February, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil futures were trading at more than 49 USD/barrel. That is up from late January’s minimum price of just over 44 USD/barrel, but still a far cry from WTI’s 2008 peak of 145 USD/barrel or the more recent peak of nearly 108 USD/barrel at the end of June. What caused this sudden downturn? What can we learn from past cycles? And what impact will the current downturn have on the Colorado School of Mines?

“The first big rises and downturns [of my career] were controlled by outside geopolitical issues…OPEC forming and wars in the Middle East drove the prices up and down,” Dr. Ramona Graves, now dean of the College of Earth Resource Sciences and Engineering (CERSE), said.

Dean Graves earned a PhD in petroleum engineering from CSM in 1982 and has served the university ever since, first as a professor and then as head of the Petroleum Engineering Department until her promotion to dean in 2012. From this vantage point, she sees a difference in the situation compared to the past.

“Now our industry in general is more global. No one country or group of countries controls oil like it was in the past,” she said.

Dr. Bill Eustes, who worked as a field engineer with ARCO Oil and Gas before returning to academia and becoming a professor at CSM, points out the likely culprit of the most recent downturn is just economics.

“If you look at supply and demand, that’s obviously the issue. Too much supply, too little demand,” Dr. Eustes said. “Another way to say that is, we’re really too good at what we do. Everyone has come up with newer ways to extract hydrocarbons because there was a big market for it. We did such a fine job that we flooded the market.”

The United States surpassed Saudi Arabia as the leading crude oil producer in 2014, and has been the world’s leading producer of natural gas since 2010, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). This success is primarily due to the petroleum industry’s successful application of new horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing technologies to unconventional hydrocarbon reservoirs.

While production will not immediately cease as a result of the current downturn, drilling activities have slowed precipitously. The U.S. oil rig count has declined by about 39 percent, which is nearing the expected range of 40 to 60 percent quoted by Baker Hughes for previous downturns. This could lead to significant production declines in the next few years because unconventional reservoirs experience steep production declines. Continuous drilling operations are needed to keep oil flowing from these new hydrocarbon sources.

Since its inception in 1859, the oil and gas industry has been notoriously cyclical, with soaring prices followed by slumps.

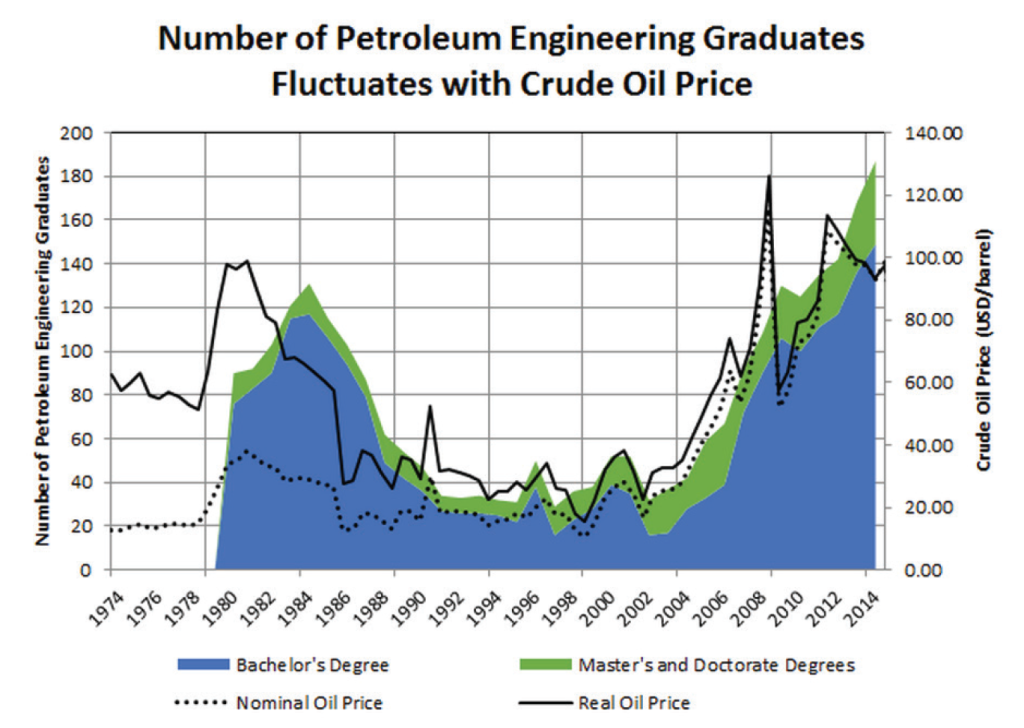

As illustrated in Figure 1, this cyclicity has been mirrored in the interest of students in petroleum engineering, albeit with a lag of a couple years. Faculty applicants are expected to increase while student interest wanes. This could provide an opportunity for the Petroleum Engineering Department and CERSE to strategically grow and take advantage of research opportunities.

This cyclicity has also been a recurring cause for concern among students completing their four-year-long educational investments of time and tuition.

“In the early 80s our classes were huge, [around] 120 students,” Dean Graves said. “They were the biggest classes we’d ever had. Then there was a downturn just like this one. At that time we were a different industry, we were a different university. All of our students had jobs in December. By January or February, about 90 percent of the students had had their job offers withdrawn. It was a horrible time.”

This lack of hiring led to a longer term problem in the industry.

“Because of the short-sightedness of a lot of companies that refused to hire during that bleak time in the late 80s and early 90s, they left that gap in the demographic that is now coming back to haunt them,” Dr. Eustes said, echoing the sentiments of many oil and gas industry veterans. “We’re not going to see quite the same cutoff that we saw with the 1980s crash, because you’ve got to keep the pipeline full to be able to keep the experience level up.”

Dr. Hossein Kazemi, Chesebro’ Distinguished Chair and professor of Petroleum Engineering, offered a hopeful perspective for students.

“Typically younger people are more protected because they have lower salaries, more potential,” Dr. Kazemi said. “Older [workers] have higher salaries and it’s easier if they are close to retirement to entice them to retire.”

This encouragement for industry veterans to retire will likely leave a dearth of experience and mentors in the increasingly youthful oilfields. However, the industry has shown signs of dealing with this issue over the years.

“The industry got smarter, and the students got smarter. There were almost no job offers withdrawn,” Dean Graves said. “They didn’t offer as many jobs, the salaries hadn’t gotten so out of line. There wasn’t such a shock.”

This is the expectation for the current cycle. Thus far, Mines has only seen three offer withdrawals confirmed with the Career Center, and they appear to be business decisions rather than knee-jerk reactions to the downturn.

“This is a real normal type of recalibrating within an industry. It is a more logical reduction in oil prices,” Dean Graves said. “I know oil prices will go up and they will stabilize. I just don’t know when and by how much.”

Service companies, who facilitate oil and gas activities rather than owning mineral resources themselves, are typically the first to cut jobs as their clients, the operators, cut back their capital expenditures.

Reuters calculates more than 100,000 layoffs announced since the price slide began last summer. Schlumberger has cut 9,000 jobs, rival Halliburton will eliminate 6,400 jobs, and Baker Hughes will lay off 7,000 employees.

The jobs that come farthest upstream in the oil and gas production process also tend to be hit hardest and fastest, as evidenced by the previously cited declining U.S. oil rig counts. Precision Drilling, a North American rig contractor, has idled a fifth of their rigs, which has left more than 1,000 workers jobless.

Students who are chilled by this news should heed the advice of their predecessors.

“One student got a job in a refinery in Roosevelt, Utah,” Dean Graves said. “He said as much as he cussed having to take thermodynamics, he suddenly knew why. Because it trained him to do other things. He was just a good engineer.”

Dr. Kazemi said he similarly remembers a graduate student well-versed in fractured reservoirs who took a job consulting for Sandia National Laboratories until he could enter the petroleum industry a year later.

Mines graduates heading for petroleum jobs may be concerned because they draw knowledge and experience only from recent history, when engineers commanded high salaries and university graduates have had their pick of multiple dream job offers.

“It’s bad for students to expend this energy and time thinking about things they can’t control. What can they control? They can control their career, what they’re involved in, their activities,” Dean Graves said. “Be smart on what you do with your electives. Become more engaged in your professional societies. Build leadership [skills]. There has to be something besides just being a petroleum engineer or just being a graduate of the School of Mines.”

Dr. Kazemi suggests that internships are a great way to get your foot in the door. Even if it takes a few years for the oil and gas industry to turn around, you will be first in line by association. He also emphasizes taking fundamental coursework seriously.

“Students really should emphasize subjects like chemistry,” he said. “An electrochemical [focus] applies to fuel cells and a pore-scale level understanding [of petroleum reservoirs]. Also, physics [is important] because of all the new devices we are using: nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), imaging, CT scanning, scanning electron microscopy (SEM). All these devices are not hard to understand, with a physics background you can relate to it.”

According to Dr. Kazemi, the more you know about the fundamentals of these new devices, you will have a lot more opportunities and options.

“Don’t get picky. You may end up in Vernal, Utah,” Dr. Eustes said. “Get your foot in the door. You can change later. You ought to take the opportunities that come up, not the opportunities that you wish for. They may not happen.”

Like Dr. Kazemi, Dr. Eustes suggests tangential industries and careers as a starting point, if necessary. Even government jobs could be beneficial.

“Having a regulatory background given today’s market and the way we do our stuff here in the States could be a very valuable asset when there is a recovery,” Dr. Eustes said.

Dean Graves encourages students to find their passion and follow it, taking advantage of the phenomenal educational opportunities at Mines.

“Even though the name [of your degree] is very narrow, you have a very broad education,” she said.

Dr. Eustes echoed a similar point.

“When you leave Mines, all we’ve really done is hand you the keys to the car. You need to learn how to drive now, that is, become an engineer,” he said. “So we’ve given you the tools, the thinking processes of being an engineer, but you’re not an engineer until you get out there and start working.”

'PE Dept. Responds to Drop in Oil Prices' has 1 comment

March 24, 2015 @ 7:13 am dave pacific

Concerned students should look at the multitude of sub-fields in civil engineering for which petroleum and geological engineers are fundamentally qualified and which can provide a good place to work and bide one’s time until the petroleum industry recovers or until a non-petroleum path becomes clear.

High school math/science is another good alternative.

The computer industry has a vast need for smart workers.

Do NOT fall into the psychological trap of ‘romanticizing’ the petroleum industry with warm and fuzzy feelings because in most cases the industry treats people like assets — drill bits, leases, offices, etc. — assets that are utilized or liquidated to meet quarterly and annual financial targets.

Note that when oil was crashing in the 1980’s the overall economy became quite strong … and similarly right now the overall economy is quite strong for people with STEM skills.